Global minimum essential requirements in medical education

CORE COMMITTEE, INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL MEDICAL EDUCATION*Institute for International Medical Education, White Plains, New York, USA

SUMMARY The process of globalization increasingly evident in medical education makes the task of defining the global essential competencies required by the 'global physicians' an urgent matter. This issue was taken up by the newly established Institute for International Medical Education (IIME). The IIME Core Committee developed the concept of 'global minimum essential requirements' (GMER) and defined a set of global minimum learning outcomes, which students of the medical schools must demonstrate at graduation. The 'Essentials' are grouped under seven broad educational domains with set of 60 learning objectives. Besides these 'global competencies', medical schools should add national and local requirements. The focus on student competences as outcomes of medical education should have deep implications for curricular content as well as the educational processes of medical schools.

Introduction

The Board of Trustees of the China Medical Board of New York, Inc. approved a grant to establish the Institute for International Medical Education (IIME) on 9 June 1999. The Institute's task is to provide the leadership in defining the 'global minimum essential requirements' ('essentials') of undergraduate medical programs. These 'essentials' were to consist of the medical knowledge, clinical skills, professional attitudes, behavior and ethics that all physicians must have regardless of where they are trained.

The task of defining the 'global minimum essential requirements' was given to the Core Committee, which comprised international medical education experts from different parts of the world. The IIME Steering Committee, consisting of eight senior education and health policy experts with broad national and international experience, advises the leadership of the Institute and helps guide the Core Committee. Further advice is provided by the IIME Advisory Committee composed of Presidents or senior representatives of 14 major international organizations active in medical education. The Committee provides a forum for information exchange, advice and helps to ensure that other efforts are complementary and not contradictory to the IIME process.

It was understood from the beginning that defining such competencies or outcomes of the medical education process would have significant implications for medical school curricula. Medical school graduates should demonstrate professional competencies which will ensure that high quality care could be provided with empathy and respect for patients' well-being.

Graduates should be able to integrate management of illness and injury with health promotion and disease prevention and be able to work in multi-professional teams. In addition, they should be able to teach, advice and counsel patients, families and the public about health, illness, risk factors and healthy lifestyles. They should be able to adapt to changing a pattern of diseases, conditions and requirements of medical practice, medical information technology, scientific advances, and changing organization of health care delivery while upholding the highest standards of professional values and ethics.

The IIME Project Consists of Three Phases:

The first phase (Phase I) 'Defining Essentials', began with the establishment of the Institute for International Medical Education. Its task was to develop a set of 'global minimum essential requirements' ('GMER') drawn in part from standards that currently exist. These standards were to include the sciences basic to medicine, clinical experiences, knowledge, skills, professional values, behavior and ethical values. These 'essentials' were to represent only the core of a medical curriculum since each country, region and medical school also has unique requirements that their individual curricula must address. Hence, each school's educational program will be different but all will possess the same core.

In the second phase(Phase II), the 'Experimental Implementation' of the 'GMER' will be used to evaluate the graduates of the leading medical schools in China. The schools will use the evaluation methods that are consistent with their experience, and have to cover all seven domains and 60 learning outcomes, to identify the strengths and deficiencies eventually found in the schools participating in this experiment. Efforts then will be made to improve all areas of weakness before a second evaluation is made. If a school meets all of the 'Essentials', it will be certified accordingly.

In the third (Phase III), or 'Dissemination Phase',the lessons learned and the process used will be modified and offered to the global medical education community for its use. Hopefully the 'essentials' will serve as a tool for improving the quality of medical education and a foundation for an international assessment of medical education programs.

Background

Globalization forces are becoming increasingly evident in medical education. This is quite natural as medicine is a global profession and medical knowledge and research have traditionally crossed national boundaries. Physicians have also studied medicine and provided services in various countries of the world. Furthermore, human creativity demands that globalization includes activities in the intellectual and cultural domains. Various multilateral agreements and conventions are opening the doors to global mobility and encouraging the development of common educational standards, mutual recognition of qualifications, and certification processes by which professionals are allowed to practice their vocation.

Presently, there are about six millions physicians worldwide, serving over six billion inhabitants. They receive their education and training in over 1800 medical schools throughout the world. Although, at first glance, global medical curricula appear similar, their content varies greatly. While there have been a number of near-successful efforts to evaluate the process leading to the MD or its equivalent degree, few of these have focused on the outcomes of their educational effort. However, there has never been an attempt to define the core or minimal competencies that all physicians should possess at the completion of their medical school training and before they enter their specialty or postgraduate training. Finally, in some countries, there has been a proliferation of new medical schools without proper assurance of educational quality.

At the same time, health services and medical practice are undergoing profound changes forced by economic difficulties in financing healthcare systems. The increasing cost of health interventions and related cost-containment policies could threaten physician's humanism and values. As a result, there is a need to preserve the goals of social benefit and equity in the face of these increasing economic pressure and constraints.

Rapid advances are occurring in biomedical sciences, information technology and biotechnology. These advances present new ethical, social and legal challenges for the profession of medicine and call for preservation of a balance between science and the art of medicine. An important task of medical education is to prepare future doctors to be able to adapt to the conditions of medical practice in a rapidly changing health care environment. The challenge before the medical education community is to use globalization as an instrument of opportunity to improve the quality of medical education and medical practice.

In defining the essential competencies that all physicians must have, an increasing emphasis needs to be placed on professionalism, social sciences, health economics and the management of information and the health care system. This must be done in the context of social and cultural characteristics of the different regions of the world. The exact methods and format for teaching may vary from school to school but the competencies required must be the same. Thus, the concept of 'essentials' does not imply a global uniformity of medical curricula and educational processes. Furthermore, the global essential requirements are not a threat to the fundamental principle that medical education has to identify and address the specific needs in social and cultural context where the physician is educated and will practice. Finally in pursuing the 'global minimum essential requirements', medical schools will adopt their own particular curriculum design, but in doing so, they must ensure that their graduates possess the core competencies envisioned in the minimum essentials. They must in short 'think globally and act locally.'

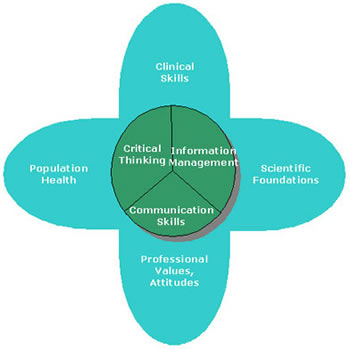

The Core Committee grouped the 'essentials' under following seven, broad educational outcome-competence domains shown in Figure 1:

Professional Values, Attitudes, Behavior and Ethics

|

Figure 1. Domains of global essential requirements |

· recognition of the essential elements of the medical profession, including moral and ethical principles and legal responsibilities underlying the profession;

· professional values which include excellence, altruism, responsibility, compassion, empathy, accountability, honesty and integrity, and a commitment to scientific methods,

· an understanding that each physician has an obligation to promote, protect, and enhance these elements for the benefit of patients, the profession and society at large;

· recognition that good medical practice depends on mutual understanding and relationship between the doctor, the patient and the family with respect for patient's welfare, cultural diversity, beliefs and autonomy;

· an ability to apply the principles of moral reasoning and decision-making to conflicts within and between ethical, legal and professional issues including those raised by economic constrains, commercialization of health care, and scientific advances;

· self-regulation and a recognition of the need for continuous self-improvement with an awareness of personal limitations including limitations of one's medical knowledge;

· respect for colleagues and other health care professionals and the ability to foster a positive collaborative relationship with them;

· recognition of the moral obligation to provide end-of-life care, including palliation of symptoms;

· recognition of ethical and medical issues in patient documentation, plagiarism, confidentiality and ownership of intellectual property;

· ability to effectively plan and efficiently manage one's own time and activities to cope with uncertainty, and the ability to adapt to change;

· personal responsibility for the care of individual patients.

Scientific Foundation of Medicine

The graduate must possess the knowledge required for the solidscientific foundation of medicine and be able to apply this knowledge to solve medical problems. The graduate must understand the principles underlying medical decisions and actions, and be able to adapt to change with time and the context of his/her practice. In order to achieve these outcomes, the graduate must demonstrate a knowledge and understanding of:

· the normal structure and function of the body as a complex of adaptive biological system;

· abnormalities in body structure and function which occur in diseases;

· the normal and abnormal human behavior;

· important determinants and risk factors of health and illnesses and of interaction between man and his physical and social environment;

· the molecular, cellular, biochemical and physiological mechanisms that maintain the body's homeostasis;

· the human life cycle and effects of growth, development and aging upon the individual, family and community;

· the etiology and natural history of acute illnesses and chronic diseases;

· epidemiology, health economics and health management;

· the principles of drug action and it use, and efficacy of varies therapies;

· relevant biochemical, pharmacological, surgical, psychological, social and other interventions in acute and chronic illness, in rehabilitation, and end-of-life care.

Communication skills

The physician should create an environment in which mutual learning occurs with and among patients, their relatives, members of the healthcare team and colleagues, and the public through effective communication. To increase the likelihood of more appropriate medical decision making and patient satisfaction, the graduates must be able to:

· listen attentively to elicit and synthesize relevant information about all problems and understanding of their content;

· apply communication skills to facilitate understanding with patients and their families and to enable them to undertake decisions as equal partners;

· communicate effectively with colleagues, faculty, the community, other sectors and the media;

· interact with other professionals involved in patient care through effective teamwork;

· demonstrate basic skills and positive attitudes towards teaching others;

· demonstrate sensitivity to cultural and personal factors that improve interactions with patients and the community;

· communicate effectively both orally and in writing;

· create and maintain good medical records;

· synthesize and present information appropriate to the needs of the audience, and discuss achievable and acceptable plans of action that address issues of priority to the individual and community.

Clinical Skills The graduates must diagnose and manage the care of patients in an effective and efficient way. In order to do so, he/she must be able to:

· take an appropriate history including social issues such as occupational health;

· perform a physical and mental status examination;

· apply basic diagnostic and technical procedures, to analyze and interpret findings, and to define the nature of a problem;

· perform appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic strategies with the focus on life-saving procedures and applying principles of best evidence medicine;

· exercise clinical judgment to establish diagnoses and therapies;

· recognize immediate life-threatening conditions;

· manage common medical emergencies;

· manage patients in an effective, efficient and ethical manner including health promotion and disease prevention;

· evaluate health problems and advise patients taking intoaccount physical, psychological, social and cultural factors;

· understand the appropriate utilization of human resources, diagnostic interventions, therapeutic modalities and health care facilities.

Population Health and Health Systems

Medical graduates should understand their role in protecting and promoting the health of a whole population and be able to take appropriate action. They should understand the principles of health systems organization and their economic and legislative foundations. They should also have a basic understanding of the efficient and effective management of the health care system. The graduates should be able to demonstrate:

· knowledge of important life-style, genetic, demographic, environmental, social, economic, psychological, and cultural determinants of health and illness of a population as a whole;

· knowledge of their role and ability to take appropriate action in disease, injury and accident prevention and protecting, maintaining and promoting the health of individuals, families and community;

· knowledge of international health status, of global trends in morbidity and mortality of chronic diseases of social significance, the impact of migration, trade, and environmental factors on health and the role of international health organizations;

· acceptance of the roles and responsibilities of other health and health related personnel in providing health care to individuals, populations and communities;

· an understanding of the need for collective responsibility for health promoting interventions which requires partnerships with the population served, and a multidisciplinary approach including the health care professions as well as intersectoral collaboration;

· an understanding of the basics of health systems including policies, organization, financing, cost-containment measures of rising health care costs, and principles of effective management of health care delivery;

· an understanding of the mechanisms that determine equity in access to health care, effectiveness, and quality of care;

· use of national, regional and local surveillance data as well as demography and epidemiology in health decisions;

· a willingness to accept leadership when needed and as appropriate in health issues.

Management of Information

The practice of medicine and management of a health system depends on the effective flow of knowledge and information. Advances in computing and communication technology have resulted in powerful tools for education and for information analysis and management. Therefore, graduates have to understand the capabilities and limitations of information technology and the management of knowledge, and be able to use it for medical problem solving and decision-making. The graduate should be able to:

· search, collect, organize and interpret health and biomedical information from different databases and sources;

· retrieve patient-specific information from a clinical data system;

· useinformation and communication technology to assist in diagnostic, therapeutic and preventive measures, and for surveillance and monitoring health status;

· understand the application and limitations of information technology;

· maintain records of his/her practice for analysis and improvement.

Critical thinking and research The ability to critically evaluate existing knowledge, technology and information is necessary for solving problems, since physicians must continually acquire new scientific information and new skills if they are to remain competent. Good medical practice requires the ability to think scientifically and use scientific methods. The medical graduate should therefore be able to:

· demonstrate a critical approach, constructive skepticism, creativity and a research-oriented attitude in professional activities;

· understand the power and limitations of the scientific thinking based on information obtained from different sources in establishing the causation, treatment and prevention of disease;

· use personal judgments for analytical and critical problem solving and seek out information rather than to wait for it to be given;

· identify, formulate and solve patients' problems using scientific thinking and based on obtained and correlated information from different sources;

· understand the roles of complexity, uncertainty and probability in decisions in medical practice;

· formulate hypotheses, collect and critically evaluate data, for the solution of problems.

To retain and advance competencies acquired in medical school, graduates must be aware of their own limitations, the need for regularly repeated self-assessment, acceptance of peer evaluation and continuous undertaking of self-directed study. These personal development activities permit the continued acquisition and use of new knowledge and technologies throughout their professional careers.

The 'Essentials' alone are not likely to change graduates' competencies unless they are linked to evaluation of students' competencies. Therefore, assessment tools for the evaluation of educational outcomes are essential for the implementation of this document. This will ensure that graduates, wherever they are trained in the world, have similar core competencies at the start of further graduate medical education (specialty training) or when they begin to practice medicine under the appropriate, nationally determined supervision. Such tools are under development by the specially established IIME Task Force for Assessment.

The presented 'Global Minimum Essential Requirements' are considered an instrument for improvement of the quality of the medical education and indirectly of the medical practice. It is hoped that the IIME project will have significant influence on medical school curricula and educational processes, paving the road to the competence-oriented medical education.

Notes on Contributors

Elizabeth G. Armstrong is Director of Medical Education at Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Raja C. Bandaranayake is Professor and Chairman of the Department of Anatomy, Arabian Gulf University College of Medicine & Medical Sciences, Manama, Bahrain.

Alberto Oriol I Bosch is Director of the Institute of Health, Department of Health and Social Security of the Catalan Government, Barcelona, Spain.

Alejandro Cravioto is Dean of the Faculty of Medicine of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico.

Charles Dohner is Professor Emeritus of Medical Education at the University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

Marvin R. Dunn is Chairman of the Core Committee of the Institute for International Medical Education and Director of Residency Review Committee Activities for the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, Chicago, IL, USA.

Joseph S. Gonnella is Director of the Center for Research in Medical Education and Health Care and Dean Emeritus of Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, PA, USA.

John D. Hamilton is Academic Director, Undergraduate Curriculum in Medicine at the University of Durham, Stockton Campus, Stockton-on-Tees, UK and formerly Professor of Medicine at the University of Newcastle, Australia.

Ronald M. Harden is Vice Dean for Medical Education and Director of the Center for Medical Education at the University of Dundee. He also holds the post of Secretary General of the Association for Medical Education in Europe, Dundee, Scotland, UK.

David Hawkins is Executive Director of the Association of Canadian Medical Colleges in Ottawa, Canada.

José Felix Patiño is President of the National Academy of Medicine, Bogotá, Colombia.

M. Roy Schwarz is President of the China Medical Board of New York, Inc. and Professor at the University of Washington and University of California at San Diego. He is also Chairman of the IIME Steering and Advisory Committees in New York, USA.

David T. Stern is Chairman of the Task Force for Assessment for the Institute for International Medical Education. He also holds the positions of Assistant Professor of Medicine and Director of Standardized Patient Programs at the University of Michigan Medical Center in Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Prasong Tuchinda is Dean of the Faculty of Medicine of Rangsit University and President of the General Practitioners/Family Physicians Associations Thailand, Bangkok, Thailand.

J.P. De V. Van Niekerk is Dean Emeritus of University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa.

Andrzej Wojtczak is Director of the Institute for International Medical Education in New York and Professor in the School of Public Health and Social Medicine in Warsaw. Previously, he was Director of the WHO Research Centre for Health in Kobe, Japan and held the position of AMEE President.

Zhou Tongfu is Vice Director of the Bureau of Education of Sichuan Province and Professor of Sichuan University Medical Center in Chengdu, People's Republic of China.

Bibliography

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) (1999) Outcome Project & General Competencies.

Accreditation and the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (1998) Functions and Structure of a Medical School, Standards for Accreditation of Medical Education Programs Leading to the M.D. Degree (Washington, D.C., Association of Medical Colleges and the American Medical Association).

American Medical Association (1993) The Potential Impact of Health System Reform on Medical Education (Working Group on Medical Education and Health System Reform, Office of Medical Education).

Association of American Medical Colleges (1984) Physicians for the Twenty-First Century, The GPEP Report, Report of The Panel on the General Professional Education of the Physician and College Preparation for Medicine (Washington, D.C., AAMC).

Association of American Medical Colleges and American Medical Association (1997) Guide to the Institutional Self-Study - Program of Medical Education Leading to the MD Degree (Chicago, IL and Washington, D.C., Liaison Committee on Medical Education).

Association of American Medical Colleges and American Medical Association (1998) The Role of Students in the Accreditation of U.S. Medical Education Programs (Chicago, IL and Washington, D.C., Liaison Committee on Medical Education).

Association of American Medical Colleges and American Medical Association (1998) Rules of Procedure (Chicago, IL and Washington, D.C., Liaison Committee on Medical Education).

Association for Medical Education in Europe (1999) A Critical Appraisal of Medical Education. Abstracts of AAME Conference, Linkpoing, Sweden, 29 August to 1 September 1999 (Dundee, Scotland, AMEE).

Association for Medical Education in Europe (1996) AMEE Education Guide No. 7: Task-based Learning: An Educational Strategy for Undergraduate, Postgraduate and Continuing Medical Education (Dundee, Scotland, AMEE).

Association for Medical Education in Europe (1999) AMEE Education Guide No. 14: Outcome-based Education (Dundee, Scotland, AMEE).

Australian Medical Council Inc. (1992) The Assessment and Accreditation of Medical Schools by the Australian Medical Council (Australian Medical Council Incorporated).

Bandaranayake, R. (2000) The Concept and Practicability of a Core Curriculum in Basic Medical Education, Medical Teacher 22(6), p. 560.

Boelen, C. (1995) Prospects for Change in Medical Education in the Twenty-first Century, Academic Medicine 70(7), p. S21 (WHO/ECFMG Conference, October 3-6, 1994, Geneva, Switzerland).

Branch, W.T. (2000) The Ethics of Caring and Medical Education, Academic Medicine 75(2), p. 127.

CanMEDS 2000 (1996) Project Skills for the new millennium: report of the societal needs working group, The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada's Canadian Medical Education Directions for Specialists 2000 Project (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada).

CanMEDS 2000 (2000) Extract from the CanMEDS 2000 Project Societal Needs Working Group Report (2000), Medical Teacher 22(6), p. 549.

Chaves, M.M. et al. (1984) Cambios en la education medica. Analisis de la integracion docente asistencial en America Latina (Caracas, Venezuela, Federacion Panamericana de Asociaciones de Facultades y Escuelas, No. 3).

DeAngelis, C.D. (Ed.) (1999) The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Curriculum for the Twenty-first Century (Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press).

DelVecchio Good, M. (1995) American Medicine: The Quest for Competence (Berkeley, University of California Press).

Education Committee of the General Medical Council (1993) Tomorrow's Doctors: Recommendations on Undergraduate Medical Education (London, General Medical Council).

Eitel, F. and Steiner, S. (1999) Evidence-based learning, Medical Teacher 21(5), p. 506.

Federacion Panamericana de Asociaciones de Facultades (Escuelas) de Medicina No. 13 (1986) Cooperacion internacional para el desarrollo de la educacion medica (Caracas, Venezuela).

Federacion Panamericana de Asociaciones de Facultades (Escuelas) de Medicina No. 17 (1990) Medical Education in the Americas. The challenge of the nineties, Final Report of the EMA project. p. 240 (Caracas, Venezuela).

Flexner, A. (1910) Medical Education in the United States and Canada. A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. (Boston, MA, D.B. Updike, The Merrymount Press).

Gastel, B.A. (1995) Toward a Global Consensus on Quality Medical Education: Serving the Needs of Populations and Individuals: Summary of the Consultation, Academic Medicine, 70(7), p. S3 (WHO/ECFMG Conference, 3-6 October, 1994, Geneva, Switzerland).

General Medical Council (1998) Good Medical Practice (General Medical Council. London).

Goldie, J. (2000) Review of ethics curricula in undergraduate medical education, Medical Education, 34, p. 108.

Gonnella, J.S., Hojat, M., Erdmann, J.B. (1993) What we have learned, and where do we go from here? Academic Medicine, 68(2), p. S79.

Halpern, R. et al. (2001) A Synthesis of Nine Major Reports on Physicians' Competencies for the Emerging Practice Environment, Academic Medicine, 76(6), p. 606.

Hamilton, J.D., Vandewerdt, J.M. (1990) The accreditation of undergraduate medical education in Australia, Medical Journal of Australia,153, p. 541.

Hamilton, J.D. (1995) Establishing Standards and Measurement Methods for Medical Education, Academic Medicine, 70(7), p. S51.

Henry, R. (1997) Undergraduate programme objectives: the basis for learning and assessing by domain, in: R. Henry, K. Byrne and C. Engel (Eds.) Imperatives in Medical Education, pp. 18-23 (Callaghan, NSW., Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, The University of Newcastle).

Institut d'Estudis de la Salut (1997) Professional Competencies on Health Sciences. Future scenario for the health professionals (Barcelona, Spain).

Karle, H., Nystrup, J. (1996) Evaluation of Medical Specialist Training: Assessment of Individuals and Accreditation of Institutions. Association for Medical Education in Europe Occasional Paper No. 1 (Dundee, Scotland, Centre for Medical Education).

Kern, D.E. et al. (1998) Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six-Step Approach (Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press).

Lloyd, J.S. (Ed.) (1982) Evaluation of noncognitive skills and clinical performance (American Board of Medical Specialties, Chicago, Illinois).

Ludmerer, K.M. (1999) Time to Heal - American Medical Education from the Turn of the Century to the Era of Managed Care. (New York, Oxford University Press).

Medical School Objectives Working Group (1999) Learning Objectives for Medical Student Education-Guidelines for Medical Schools: Report I of the Medical School Objectives Project. Academic Medicine,74(1), p. 13.

National Association of Medical Students (1994) Today's Students on "Tomorrow's Doctors" A Guide to Implementing the General Medical Council Recommendations on Undergraduate Medical Education (National Association of Medical Students).

O'Neill, P.A., Metcalfe, D., and David, T.J. (1999) The core content of the undergraduate curriculum in Manchester, Medical Education, 33, p. 121.

Paice, E. (Ed.) (1998) Delivering the New Doctor. (Edinburgh, Scotland, Association for the Study of Medical Education).

Rabinowitz, H.K. et al. (2001) Innovative approaches to educating medical students for practice in a changing health care environment: the National UME-21 Project, Academic Medicine, 76(6), p. 587.

Sajid, A. et al. (Eds.) (1994) International Handbook of Medical Education (Westport, CT, Greenwood Press).

Schwarz, R.M. (1998) On moving towards international standards in health professions education. Changing Medical Education and Medical Practice (WHO, Geneva, Switzerland).

Scott, C.S. et al. (1991) Clinical behavior and skills that faculty from 12 institutions judged were essential for medical students to acquire, Academic Medicine, 66(2), p. 106.

Sprafka, S. (1999) Defining and using professional behavior standards: an approach underway at the University of New England, Education for Health, 12(2), p. 245.

Stobo, J.D., Blank, L.L. (1998) Project Professionalism: Staying Ahead of the Wave (American Board of Internal Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania).

Swanson, A.G., Anderson, M.B. (1993) Educating medical students, assessing change in medical education - the road to implementation, Academic Medicine, 68(6), Supplement.

Tosteson, D.C., Adelstein, S.J., Carver, S.T. (Eds.) (1994) New Pathways to Medical Education (Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press).

University of Dundee Medical School (n.d.) Teaching Tomorrow's Doctors in Dundee - A five-year strategy 1999-2003 (Dundee, Scotland, University of Dundee Medical School).

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (1992) Council on Graduate Medical Education, Third Report: Improving Access to Health Care Through Physician.

Wojtczak, A. and Schwarz, M.R. (2000a) International standards and medical education: discussion document.

Wojtczak, A. and Schwarz, M.R. (2000b) Minimum essential requirements and standards in medical education, Medical Teacher, 22(6), p. 555.

World Federation for Medical Education Executive Council (1998) International standards in medical education: assessment and accreditation of medical schools, Medical Education, 32, p. 549.

World Federation for Medical Education Task Force (2000) Defining international standards in basic medical education, Report of the Working Party, Copenhagen 1999, Medical Education, 34(8), p. 665.

World Federation for Medical Education (1994) Proceedings of the World Summit on Medical Education. Ed. Henry Walton, Medical Education, Vol. 28, Suppl. 1.

World Health Organization (1992) Towards the Assessment of Quality in Medical Education (Geneva, Switzerland, WHO).

World Health Organization (1993) Increasing the Relevance of Education for Health Professionals - Report of a WHO Study Group on Problem-solving Education for the Health Professionals (Geneva, Switzerland, WHO).

World Health Organization (1996) Doctors for health: A WHO Global Strategy for Changing Medical Education and Medical Practice for Health for All. (Geneva, Switzerland).

Institute for International Medical Education.

Unauthorized reproduction strictly prohibited.