The Assessment of Global Minimum Essential Requirements in Medical Education

David T. Stern

Departments of Internal Medicine and Medical Education

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

contributor notes

Andrzej Wojtczak

Institute for International Medical Education

White Plains, NY, USA

contributor notes

M. Roy Schwarz

China Medical Board of New York

New York, NY, USA

contributor notes

Based on the Work of the IIME Task Force for Assessment

Institute for International Medical Education

White Plains, New York

Full Listing of Members

Summary

Using an international network of experts in medical education, the Institute for International Medical Education (IIME) developed the "Global Minimum Essential Requirements" ("GMER") as a set of competency-based outcomes for graduating students. To establish a set of tools to evaluate these competencies, the IIME then convened a Task Force of international experts on assessment that reviewed the "GMER". After screening seventy-five (75) potential assessment tools, they identified three (3) that could be used most effectively. Of the sixty (60) competencies envisaged in the "GMER", thirty-six (36) can be assessed using a 150-item multiple-choice question (MCQ) examination, 15 by using a 15-station Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) exam, and 17 by using a 15-item faculty observation form. In cooperation with eight (8) leading medical schools in China, the MCQ, OSCE, and Faculty Observation Form were developed to be used in an assessment programme that is scheduled to be given to all 7-year students in October 2003.

"Practice Points"

This educational experiment indicates that it is possible to obtain agreement among international experts in medical education on a set of global medical competences and the means to assess them in medical graduates. The results of this pilot assessment can be used as part of a process to ensure the quality of medical schools worldwide.

Introduction

Physicians are members of a profession that is globally identifiable. However, such a profession is not sustainable without a set of core competencies that define a physician, regardless of the site of training or practice. In 1999, the China Medical Board of New York established the "Institute for International Medical Education" ("IIME") to define the minimum essential competencies that all graduates worldwide must possess if they wish to be called a physician. These minimum educational requirements were intended to form a core of outcome standards for pre-specialty medical education internationally.

This initiative has taken the form of three Phases that include following:

· Phase I:Definition of the global minimum essential requirements ("GMER") and methods to evaluate them

· Phase II: Assessment of a sample of China's leading medical schools using the "essentials" from Phase I as a reference for the evaluation

· Phase III: Sharing the results of Phases I and II with the global community of medical educators.

Phase I of the IIME Project has been completed, and the "GMER" have been defined by an international committee of expert medical educators. This "Core Committee" chose to define the minimum essentials in the form of competencies which were looked upon as outcomes of medical education. These competencies fall into seven domains:

1) professional values, attitudes, behavior and ethics

2) scientific foundation of medicine

3) clinical skills

4) communication skills

5) population health and health systems

6) management of information

7) critical thinking and research

The selection of these seven domains as priority areas was based on the conviction of committee members that they are of the crucial importance for practicing medicine in the 21st Century. Consensus was also reached on a set of global attributes to meet society's expectations in the practice of medicine. The document represents only the core requirements, since each country, region and medical school also have unique requirements that their curricula must address. Hence, each school's educational program might be different but at the core, they should all be the same (Core Committee 2002).

The "Global Minimum Essential Requirements" ("GMER") provide a set of learning outcomes for graduates of medical schools. However, the "Essentials" alone are not likely to change graduates' competencies unless they are linked to the process of evaluation. Hence, of equal, if not greater importance to defining the "GMER" was determining whether students possess these competencies at the time they complete their general medical education. In short, how can these outcomes of medical education be assessed? This paper will report on the assessment methods that will be used in the IIME Project.

The Assessment Task Force

The assessment of competencies envisioned in this project poses new challenges for medical education. Educators have commonly evaluated some competencies of medical students (e.g., history taking and clinical skills) but have rarely attempted to evaluate the entire spectrum of expected outcomes of the medical education experience, and never across multiple schools simultaneously.

To do this, the IIME assembled a Task Force made up of experts in medical education evaluation (See Annex 1) and entrusted them with the task of recommending the tools that should be used in the evaluation of the "GMER" in a developing country in multiple schools simultaneously. The Task Force on Assessment thus established a set of general principles of assessment for the purposes of this project and a matrix of recommended assessment tools for each component of the "GMER". The information and recommendations included in this document are a consensus of the opinion and ideas of the members of the Task Force.

General Principles of Assessment

Prior to assigning specific assessment tools to domains of competence, the Task Force deliberated on a set of general principles of assessment. These principles included the concepts that assessment should ideally support the desired outcomes of medical education, that assessments should be developed in cooperation with the target schools, and that assessments are best made within the context of what outcomes will be expected. Such guiding principles guarantee that the tools developed will be both relevant and not counterproductive to the overall educational effort.

In addition to these general principles, the IIME project is focused on measuring the best possible outcomes of education at the medical school level, rather than the individual student level. For this reason, the Task Force agreed that assessment at the exit point (medical school graduation) is preferred, understanding that some assessments will be made over a period of time and submitted upon exiting from medical school. This principle ensures that graduates are departing with these competencies, rather than measuring some intermediate competency. For example, while knowledge of basic principles of pathophysiology may be necessary to understand and manage diabetic nephropathy, it is the latter condition that constitutes the measurement outcome of interest for this project.

An assumption of this work is that the assessment of curriculum can be achieved by sampling the medical student "outcomes" from an individual medical school. In that way, while medical students are the medical education "outcome" of interest for this project, each student constitutes a sample of the effect of the educational experience including the curriculum. The implications of this principle is that not all students would necessarily need to be evaluated on every domain, thereby providing an opportunity, though not the necessity, for cost-savings. In addition, the Task Force concluded that the measurement of different outcome competencies could be made by assessing different students and the results amalgamated for a snapshot of an entire school's educational success.

Because there are some domains for which there is no one, single, best assessment tool, it is likely that the triangulation of assessment methods may be necessary. For example, the assessment of communication skills might be evaluated through the use of multiple choice questions, a standardized patient/OSCE experience, and through the use of faculty observations of student behavior in clinical care situations. Although it should be clear from use of the term "outcome assessment," and from the overall intent of the IIME project, that the outcomes themselves are expected to be criterion-rather than norm-referenced. There is a core foundation of knowledge, skills, and behaviors expected of physicians internationally, and the standard for these elements should not be influenced by the average competency of graduating students, but rather, by expectations of the educators.

Grouping of Requirements by Assessment Tool

Having determined the purpose and philosophy of this evaluation project, the Task Force identified the measurement methods that would be congruent with the expected competencies. The choice of measurement methods and construction of measurement instruments is a crucial step in the evaluation process because it provides the link between student performance and expected outcomes. If the assessment methods are inappropriate, or if there is imbalance between theoretical knowledge assessment and clinical assessment, unfortunate learning consequences for students and curriculum may occur. Equally importantly, if the assessments are of low quality, wrong decisions could be made which might be detrimental to the future of the students or to the welfare of the community.

From the beginning of the evaluation process, it was abundantly clear that the sixty "GMER" learning objectives could be evaluated using many different assessment tools. The specific purpose of the Task Force was to propose a limited number of tools that are both economically feasible and educationally adequate for the task of assessing the "GMER". The assessments which will be used may not be the best or the only methods of assessing each competency, but it are hoped that they provide a credible framework on which a program of assessment could be developed.

In a brainstorming session, the Task Force imagined over seventy (70) different tools that could be used for this project. This list was narrowed to three based on: 1) the established reliability and validity of the tool; 2) the practicality for implementing the assessment at multiple sites; and 3) the cost. While the tools not chosen were felt to be both feasible and adequate for the task of assessing the "GMER", the three chosen best met the criteria established for Phase II of the project. However, it was understood and accepted that the three tools could be replaced by others as the technology and science of assessment evolves and develops.

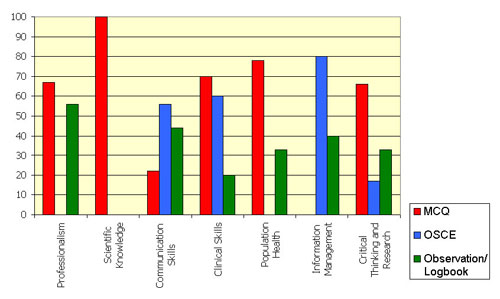

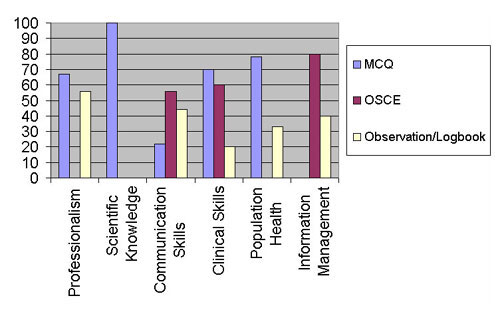

The three assessment tools for this project are: 1) a Multiple-Choice written examination (MCQ), 2) an Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) using patient and bench simulations with post-interaction exercises, and 3) Observer (faculty, peer, nurse, or patient) ratings of performance and Logbook of students' learning experiences. Of the sixty (60) "GMER", 36 can be assessed by MCQ, 17 by OSCE, 14 by observer ratings, and 4 by logbooks. Included in this enumeration are seven items that are to be assessed by both MCQ and OSCE, one by MCQ and observer rating, one by MCQ and Logbook, and two by OSCE and Logbook. The sixty (60) "GMER" are listed in Tables 1-4, categorized by the assessment tool identified as most appropriate. Figure 1 provides a depiction of the percentage of each "GMER" domain assessed by each tool.

Phase II of the IIME Project

Eight leading medical schools in China have sent delegates to three workshops in preparation for Phase II of the project, i.e. the assessment of competencies. Each school has a representative who is charged with leading the implementation of Phase II scheduled for October 2003, and each of these leaders is working in their home institution to develop the assessment team necessary to complete this evaluation. This project is the largest simultaneous, identical outcome assessment of multiple schools project ever attempted. It opens a new era of educational accountability for medical schools, and helps to ensure that the quality of physicians worldwide meets a global standard for excellence.

Discussion

It was understood from the beginning that defining and assessing outcomes in medical education would have significant implications for medical school curricula. Although the project will evaluate students, the IIME will aggregate student results to provide individual schools with data about its relative strengths and weaknesses. This report can then be reviewed by medical educators to alter the learning experiences they provide. Prior to a repeat evaluation, schools would be expected to improve areas of weakness, and share areas of strength with other schools. If a school meets all of the essential requirements, they will be certified as having done so by the IIME. This is intended to be an iterative process of continuous improvement based upon the experiences gained through the evaluation itself.

The IIME activity is a developing, living process, guided by the input and ideas of worldwide medical education experts. The "GMER" are intended as a starting point which future generations of physicians can (and should) adapt and improve as the practice of medicine, the science upon which it is based and educational theory and technology improves. For example, the current "GMER" domain "Management of Information," is a competency that few would have identified prior to the information revolution of the late 20th Century. Similarly, the process of assessment underway in China is not the gold standard for all time. Instead, as assessment technology changes and as existing tools become more feasible, this process of evaluation may be altered. In recent years, the development of new assessment methods such as the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE), the portfolio approach, standardized patient examinations, and computer case simulations have permitted us to assess the competences envisaged in the "GMER". While assessment tools may change over time, what will not change is the insistence that only the best available and feasible tools be used to evaluate the "GMER" outcomes.

References

1. Ben-David Friedman M. (2000) Standard setting in student assessment AMEE Education guide #18, Medical Teacher; 22(2):120-130.

2. Case S, Swanson D. (1998) Constructing written test questions for the basic and clinical sciences. 2nd Edition, National Board of Medical Examiners.

3. Collins JP, Harden RM. (1998) The use of real patients, simulated patients, and simulators in clinical examinations, AMEE Education Guide #13, Medical Teacher; 20(6):508-521.

4. Core Committee, Institute for International Medical Education. (2002) Global minimum essential requirements in medical education, Medical Teacher 24, (2) 130-135.

5. Hamilton JD. (2000) International Standards of Medical Education: A Global Responsibility. Editorial, Medical Teacher, 22 (6) 547-8.

6. Harden RM, Crosby JR & Davis MH. (1999) An introduction to outcome-bases education, Medical Teacher 21 (1):7-14.

7. Schwarz MR. (2001) Globalization and medical education, Editorial, Medical Teacher 23 (6).

8. Schwarz MR. (1998) On moving towards international standards in health professions education, Changing Medical Education and Medical Practice, World Health Organization, Geneva.

9. Schwarz MR., Wojtczak A. (2002)Global minimum essential requirements: a road towards competence-oriented medical education, Medical Teacher 24 (2), 125-129.

10. Streiner DL, Norman GR. (1996)Health Measurement Scales: A practical guide to their development and use. Oxford University Press, Oxford [England].

11. Wass V, Van der Vleuten CPM, Shatzer J, Jones R. (2001)Assessment of clinical competence. Lancet; 357:945-949.

12. Wojtczak A, Schwarz MR. (2000) Minimum essential requirements and standards in medical education, Medical Teacher, 22, (6) 555-9.

13. Wojtczak A, Schwarz MR. (2001) International Standards in Medical Education: what they are, and do we need them? Presented at the AMEE Conference, September 2-5, Berlin, Germany.

14. World Federation for Medical Education Task Force. (2000) Defining international standards in basic medical education, Report of a Working Party, Copenhagen 1999, Medical Education, 34 (8) 665-75.

15. World Health Organization/Education Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates. (1995) Towards a global consensus on quality medical education; serving the needs of population and individuals, Proceedings of the 1994 WHO/ECFMG Consultation in Geneva, Switzerland, Academic Medicine, 70 (7, Suppl.).

The above references were selected from a very extensive literature list on assessment in education as particularly useful and relevant for understanding the scope of IIME project and planning its evaluation program.

Annex 2

Table 1. GMER Items assessed by multiple-choice examination (n = 36)

Professional Values, Attitudes, Behaviors and Ethics (n = 6/11)*

Professional Values, Attitudes, Behaviors and Ethics (n = 6/11)*

- Recognition of the essential elements of the medical profession, including moral and ethical principles and legal responsibilities underlying the profession

- An understanding that each physician has an obligation to promote, protect, and enhance these elements for benefit of patients, the profession and society at large

- Recognition that good medical practice depends on a mutual understanding and relationship between the doctor, the patient and the family with respect for patient's welfare, cultural diversity, beliefs and autonomy

- An ability to apply the principles of moral reasoning and decision-making to conflicts within and between ethical, legal and professional issues including those raised by economic constrains, commercialization of health care, and scientific advances

- Recognition of the moral obligation to provide end of life care, including palliation of symptoms

- Recognition of ethical and medical issues in patient' documentation, plagiarism, confidentiality and ownership of intellectual property

Scientific Foundation of Medicine (n = 10/10)

- The normal structure and function of the body as a complex of adaptive biological system

- Abnormalities in body structure and function which occur in diseases

- The normal and abnormal human behavior

- Important determinants and risk factors of health and illnesses and of interaction between man and his physical and social environment

- Molecular, cellular, biochemical and physiological mechanisms that maintain the body's homeostasis

- The human life cycle and effects of growth, development and aging upon the individual, family and community

- The etiology and natural history of acute illnesses and chronic diseases

- Epidemiology, health economics and health management

- The principles of drug action and it use, and efficacy of varies therapies

- Relevant biochemical, pharmacological, surgical, psychological, social and other interventions in acute and chronic illness, in rehabilitation, and end-of- life care.

Communication Skills (n = 2/9)

- Apply communication skills to facilitate understanding with patients and their families and to enable them to undertake decisions as equal partners

- Communicate effectively both orally and in writing

Clinical Skills (n = 7/10)

- Apply basic diagnostic and technical procedures, to analyze and interpret findings, and to define the nature of a problem

- Exercise clinical judgment to establish diagnoses and therapies

- Recognize immediate life threatening conditions

- Manage the common medical emergencies

- Manage of patients including health promotion and disease prevention in an effective, efficient and ethical manner the care of patients including health promotion and disease prevention

- Evaluate health problems and advise patients taking into account of physical, psychological, social and cultural factors

- Understand appropriate utilization of human resources, diagnostic interventions, therapeutic modalities and health care facilities

Population Health and Health Systems (n = 7/9)

- Knowledge of important life-style, genetic, demographic, environmental, social, economic, psychological, and cultural determinants of health and illness of a population as a whole

- Knowledge of their role and ability to take appropriate action in disease, injury and accident prevention and protecting, maintaining and promoting the health of individuals, families and community

- Knowledge of international health status, of global trends in morbidity and mortality of chronic diseases of social significance, the impact of migration, trade, and environmental factors on health and the role of international health organizations

- Understanding the need for collective responsibility for health promoting interventions which requires partnership with the population served, and a multidisciplinary approach including the health care professions as well as intersectoral collaboration

- An understanding of the basics of health systems including policies, organization, financing, cost-containment measures of rising health care costs, and principles of effective management of health care delivery

- An understanding of the mechanisms that determine equity in access to health care, effectiveness, and quality of care

- The use of national, regional and local surveillance data as well as demography and epidemiology in health decisions

Critical Thinking and Research (n = 4/6)

- Understand the power and limitations of the scientific method including accuracy and validity of scientific information in establishing the causation, treatment and prevention of disease including

- Identify, formulate and solve patients' problems using scientific thinking and based on obtained and correlated information from different sources

- Understand the role of complexity, uncertainty and probability in decisions in medical practice

- Formulate hypotheses, collect and critically evaluate data for the solution of problems.

* n = number to be assessed out of total competencies in each domain, e.g.; 14/17 would mean 14 assessed by this method out of a total 17 competencies in this domain.

Table 2: GMER items assessed by OSCE (n = 17)

Communication Skills (n = 5/9)

Communication Skills (n = 5/9)

- Listen attentively to elicit and synthesize relevant information about all problems and understanding of their content

- Apply communication skills to facilitate understanding with patients and their families and to enable them to undertake decisions as equal partners

- Demonstrate sensitivity to cultural and personal factors that improve interactions with patients and the community

- Communicate effectively both orally and in writing

- Synthesize and present information appropriate to the needs of the audience, and discuss achievable and acceptable plans of action that address issues of priority to the individual and community.

Clinical Skills (n = 7/10)

- Take an appropriate history including social issues such as occupational health

- Perform a complete physical and mental status examination

- Perform appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic strategy with focus on life saving procedures applying principles of best evidence medicine

- Recognize immediate life threatening conditions

- Manage the common medical emergencies

- Manage of patients including health promotion and disease prevention in an effective, efficient and ethical manner the care of patients including health promotion and disease prevention

- Evaluate health problems and advise patients taking into account of physical, psychological, social and cultural factors

Management of Information (n = 4/5)

- Search, collect, organize and interpret health and biomedical information from different databases and sources

- Retrieve patient-specific information from a clinical data system

- Use information and communication technology to assist in diagnostic, therapeutic and preventive measures, and for surveillance and monitoring health status

- Understand application and limitations of information technology

Critical Thinking and Research (n = 1/6)

- Formulate hypotheses, collect and critically evaluate data for the solution of problems.

Table 3: GMER items assessed by observer ratings (n=14)

Professional Values, Attitudes, Behaviors and Ethics (n = 5/11)

Professional Values, Attitudes, Behaviors and Ethics (n = 5/11)

- Professional values which include excellence, altruism, responsibility, compassion, empathy, accountability, honesty and integrity, and a commitment to scientific methods

- Self-regulation and a recognition of the need for continuous self-improvement with an awareness of personal limitations including limitations of one's medical knowledge

- Respect for colleagues and other health care professionals and the ability to foster a positive collaborative relationship with them

- Ability to effectively plan and efficiently manage one's own time and activities to cope with uncertainty, and the ability to adapt to change

- Personal responsibility for the care of individual patient.

Communication Skills (n = 4/9)

- Communicate with colleagues, faculty, the community, other sectors and the media

- Interact with other professionals involved in patient care through effective teamwork

- Demonstrate basic skills and positive attitudes towards teaching others

- Create and maintain good medical records

Population Health and Health Systems (n = 3/9)

- Knowledge of their role and ability to take appropriate action in disease, injury and accident prevention and protecting, maintaining and promoting the health of individuals, families and community

- An acceptance of the roles and responsibilities of other health and health related personnel in providing health care to individuals, populations and communities

- Willingness to accept leadership when needed and as appropriate in health issues.

Critical Thinking and Research (n = 2/6)

- Demonstrate a critical approach, constructive skepticism, resourcefulness, and a research-oriented attitude in professional activities

- Use personal judgments for analytical and critical problem solving and seek out information rather than to wait to be given

Table 4: GMER items assessed by logbook (n=4)

Clinical Skills (n = 2/10)

- Apply basic diagnostic and technical procedures, to analyze and interpret findings, and to define the nature of a problem

- Perform appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic strategy with focus on life saving procedures applying principles of best evidence medicine

Management of Information (n = 2/5)

- Use information and communication technology to assist in diagnostic, therapeutic and preventive measures, and for surveillance and monitoring health status

- Maintain records of own practice for analysis and improvement

Figure 1: Percentage of Each GMER Domain Assessed by Test Type*

(*Totals more than 100% per domain as some GMER items are assessed by multiple testing types)

Figure 2: Percentage of Each GMER Domain Assessed by Test Type*

(*Totals more than 100% per domain as some GMER items are assessed by multiple testing types)

Institute for International Medical Education.

Unauthorized reproduction strictly prohibited.